Alcohol

Recovery

How long before I stop thinking about drink?

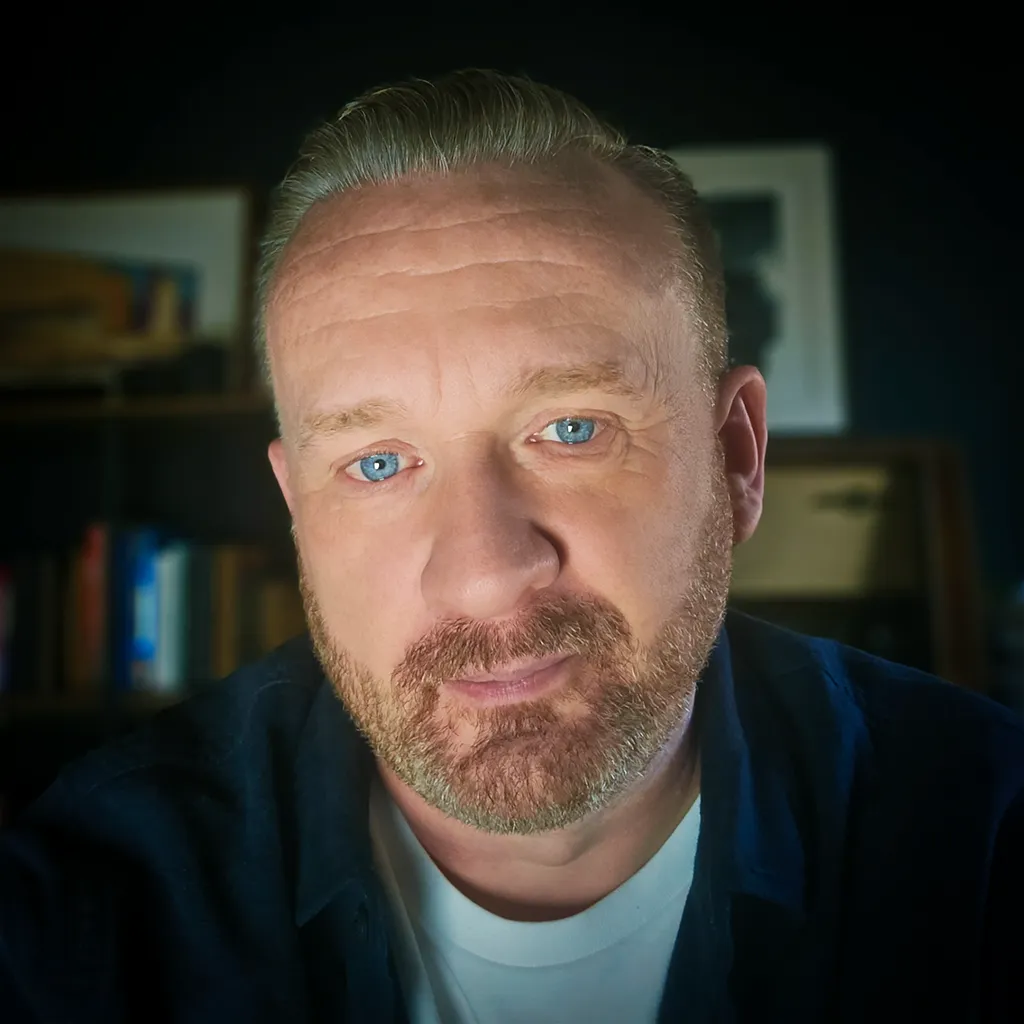

by John Risby

Published: February 01, 2021 Last updated: November 30, 2023

Question

How long until you don’t think about alcohol anymore?! How long before you’re truly at peace from it?!This is one of those questions I truly wish I had a simple answer for. It would be great to be able to say it’s a fixed period – a week, a month, even a year – and that’s it, job done, the desire to drink is gone for good. Alcohol becomes a distant memory and you can move on without worry.

Of course, you know what’s coming next. I don’t have a simple answer. And no one does.

Some may claim they do, but if anyone claims an easy fix for alcoholism, the chances are it comes with strings – financial or otherwise – and you’re best avoiding them like Covid.

Alcohol addiction is a complex issue, and one that isn’t even fully understood.

Unlike most conditions with universally accepted treatments – for instance, most accept what causes blood pressure and what lifestyle changes and medication helps – alcoholism, its causes and the best way to treat it are still disputed by many.

The disease model of alcoholism

Various bodies such as the American Medical Association and others, have classified alcoholism as a disease for many years, but that isn’t accepted by all – including by some medical professionals and some who work in alcohol services.

Historically this model of addiction was first discussed in the 19th century and adopted in the early part of the 20th century in the UK. The alternative was to treat addictions such as alcoholism as a judicial matter and to punish addicts rather than try to treat them medically, something that continued for many years with other drugs.

Numerous studies have shown there are so many factors involved – from genetics, lifestyle choices, upbringing, childhood trauma etc – that a consensus is hard to reach.

And the way alcohol affects the body and mind on a physical level leaves the debate even more open. Alcohol use, especially heavy use, leads to chemical changes in the structure of the brain, and especially in the prefrontal cortex which is vital for decision making. The damage to this area can make it harder for an alcoholic to realise the severity of their problem and to make the changes needed to tackle it. Even waking up with a hangover on a regular basis is often not enough to change our relationship with booze. This has led those in the field of neuroscience to classify alcoholism as a chronic relapsing brain disease.

Enter Alcohol Use Disorder

In recent years the term to refer to problem drinking has changed to Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) instead of alcoholism, but changing labels doesn’t change the problems.

Alcohol Use Disorders also include various levels of alcohol misuse from mild, moderate, and severe, including up to alcoholism. Possibly someone thought it was a politically correct thing to do, but I can’t help but think it could cause more problems than it solves by lumping together those who have a genuine concerns over a bottle of wine or two a week, which can still be a valid problem, with those who constantly have no recollection of what they have done, and ruin relationships, jobs and their health – as well as everyone between these extremes.

Alcoholism, and all levels of alcohol misuse, is dangerous but the amounts of alcohol, the levels of alcohol content, and peoples’ drinking habits make a big difference in the treatment and prognosis.There’s not even an an accepted test to decide if someone is an alcoholic. There are guidelines and criteria set out in the International Classification of Diseases, published by the World Health Organisation, although even these do not recognise addiction as a diagnostic term. It does however have criteria for Dependence Syndrome. But, again, it’s often hard to differentiate between casual, moderate, and heavy drinkers.

Ultimately no one person can say with certainty that another person is an alcoholic. It would be a case of ask ten doctors, get five diagnoses, at least. A combination of medical experience and the individual persons own feelings is a more accurate guide, and – crucially – the latter is more important in treating any type of addiction.

If the drinker does not accept they have a problem, successful treatment is unlikely.

And for a lot of alcoholics, heavy drinking is tied up with other mental health issues which can make recovery even harder.

That’s all very good, but can you answer the question please?

Ok, so that’s a brief and somewhat simplistic overview of some of the science behind alcoholism, but what about the question. How long until one stops thinking about alcohol and finds true inner peace?

The sad fact is some people never stop thinking about alcohol and face a constant daily battle for the rest of their lives to avoid pouring a glass of wine, buying a bottle of vodka, or grabbing a six-pack of beers while shopping. Yet others quickly get to the point where they have accepted they can’t drink, and – through something as simple as simply saying “I don’t drink alcohol”, move on with their lives and hardly give it another thought.

In my experience of both being a sober alcoholic of 16 years, and knowing and working with many alcoholics and problem drinkers over the years, there’s no obvious unifying link behind their success stories.

Some attend AA meetings, some don’t. Some have comfortable lives without money worries and with good health, some lead lives of poverty, stress, depression, and illness.

And the same applies in the opposite to those who struggle to stay sober. Some people with outwardly great lives struggle to stop, while some who live in a more challenging environment find the process much easier, and go on to lead a better life without alcohol. It really does vary person to person.

But even for those who do successfully move on, it’s impossible to never think about drink. Even if you wanted to, it’s everywhere in society. Whether on tv, sports, friends – it’s hard to go a day without being reminded of the booze.

What matters is how we think about it. That’s what leads to us making the right decisions and staying in control. Going back to the simple phrase ‘I don’t drink’, that’s a great way to reply to people when they ask you if you want a drink at a party or in the pub. In the early days it may be easier to come up with less permanent reasons such as being on a diet or taking medication, or that you’re driving. But when you’re more comfortable with your decision to stop drinking alcohol and you feel more confident, it’s a good phrase to adopt. It’s a definitive statement of fact and it makes wavering on the issue less likely.

My own experience

For me, I’d say the first year was the hardest in terms of thinking about drink. I did go to AA in that first year, and found it a great help, but it also lead to some problems. I was determined I wouldn’t let my problem stop me from leading a normal life, which included going to the pub with friends and family. But for that first year while going to AA, and for some time afterwards, I became paranoid going into a pub in case I was seen by someone from a meeting and they thought I had relapsed. Now I look back and, almost, laugh at the idea but back then it was a very stressful position to be in.

I always make it clear that AA helped me in that first year, and I have no idea if I couldn’t have done it without them, but long-term it wasn’t for me. I do encourage anyone with a problem to at least try a couple of meetings (not all meetings are good so please don’t be put off by the first one if you don’t like it).

Eventually I found my own way to cope. Some in AA would – and have – labelled me a ‘dry drunk’ (an offensive term for people who are just as sober as those throwing the accusation around, but who choose to lead their life in a way the accusers don’t, or in some cases perhaps, can’t). At my stage, it’s not something I particular worry about too much, but it’s still frustrating to be judged.

Keeping secrets causes stress

I kept my alcoholism secret for several years after stopping. Only close friends and family knew – officially anyway. But after about seven years I decided it really didn’t matter. I had been running The Alcohol-Free Shop since 2006, and had been sober since 2004. Why should I be worried what people thought?

I think being open about my alcoholism and recovery actually helped me think about it less. Even though it meant I spoke more about it, wrote more about it, and was more actively involved in helping others, it didn’t make me think about drinking more at all.

This is a bit like the old joke about how you always find your keys in the last place you look, but in 2004 when I did stop for good, I’d made several attempts to quit and failed. But so far so good and it’ll be 17 years in June.

In those years I’ve gone through bad and stressful episodes such as losing my father, divorce, a business failure, etc, and good events too – moving to Spain, rebuilding the business, remarrying, and having a wonderful daughter. Through all those moments, I’ve survived without ever giving drink a serious thought. I did, however, start smoking again briefly and I’m still vaping now several years later… But that’s another thing to tackle at some point.

Had any of those events happened in the first year of getting sober perhaps it would have been different, but I like to believe things happen, and happen at certain times, for a reason. And I’ve certainly been lucky to have been able to cope through all these situations without a drink.

Whichever way you want to describe it – a disease, a mental illness, an addiction etc, alcoholism is a serious and progressive condition and the effects of excessive alcohol consumption cause many serious illnesses and premature death. And while it’s understandable to want to jump to the acceptance stage as soon as possible, it will happen in its own time if that is what is meant to be, and if you put the work in to make it so.

So, how long can I expect it to take?

The physical symptoms of alcohol-withdrawal pass very quickly. A week or so and you are no longer physically addicted.

The rest is ‘just’ in the mind. Of course, the mind is a wonderful, complicated, crazy, amazing thing, capable of convincing you to do things that will damage it. Thank God our legs don’t work the same way or we’d be randomly kicking brick walls!

As I approach the age of 50 this year I genuinely wonder where on earth all the years went between my first proper drink at 13 to now (sadly, a chunk of it is a blur). Life moves fast enough as it is, enjoy each day and try not to put pressure on yourself to speed up your recovery. It will happen when you are ready.

As the saying goes, life is a journey, not a destination. And for all the issues I’ve faced, and caused for others, with my drinking. I wouldn’t change my journey for the world.

If you’re lucky, you won’t even notice you’ve reached the stage where you don’t think about alcohol and you’ve found that inner peace you’re craving. It will just be how you live your life.

How much did you learn from this article?

Welcome to our article quiz! We hope you've enjoyed reading 'How long before I stop thinking about drink?' and are ready to see how much you've absorbed. Don't worry, it's meant to be fun and remember: there is no such thing as failing, only learning!

About The Author

John Risby

Co-Founder of The Alcohol-Free Shop and AlcoholFree.com. John is a recovering alcoholic who stopped drinking in June 2004. Born and raised in Manchester, he now lives in Malaga with his wife and young daughter. He came to terms with being an alcoholic many years ago, but still finds the concept his daughter is Spanish very strange.

5 Films About Alcoholism You Simply Must Watch

January 14, 2023

Celebrate your first week of sobriety – and stay motivated!

January 08, 2023

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning: How Staying Sober Can Lead to a More Productive Sunday Morning

January 07, 2023

5 Secrets to achieving Sobriety any time of year

January 03, 2023

10 Simple Tips For Your First Sober Christmas

December 23, 2021

How to cope with elderly parents drinking with dementia

February 09, 2021

What’s one thing you’re proud of since you’ve been sober?

September 21, 2020